A Nigerian artist finds a path to success where he least expected it: home.

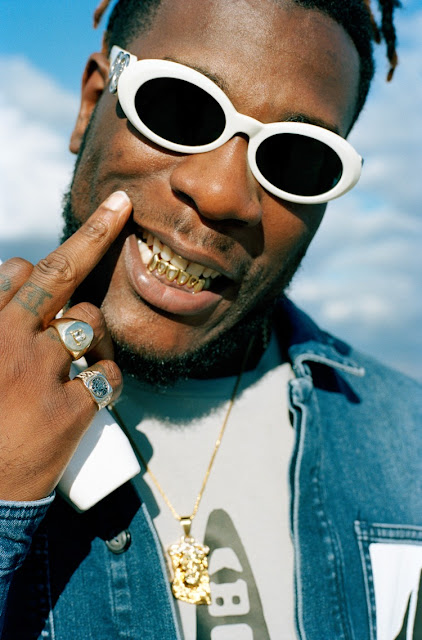

Burna Boy smoked two blunts in 20 minutes, but it wasn’t until he started singing that he finally relaxed. The British sun was making a rare, auspicious appearance through the floor-to-ceiling window of the high-rise apartment in London where he was staying during a recent visit, and it had been just a few days since he headlined the Hammersmith Apollo, but he was still all eyerolls and gruff answers when we spoke over Skype about his life and work. That is, until I asked about the new music due to follow up this fall’s Redemption EP, via his own Spaceship Entertainment label. That’s when Burna Boy closed his eyes, cocked his head back, and crooned an unreleased pidgin-and-patois anthem. For 90 sweet seconds, his prickliness melted away.

The song was a steady-paced example of the dancehall, afropop, and hip-hop mash-up — a genre he’s named “afrofusion,” and a style he takes credit for pioneering — that he’s become known for over the past few years. Like previous releases, including the 2015 single “Soke” and this summer’s “Realest,” it was a gymnastic stack of melodies, easing in and out of a handful of different flows. The lyrics were what some might describe as “woke” — aphorisms that are earnest and uplifting, if vague, sung in multiple dialects. “Dun know, dun know, tell me what has the world come to?/ Couple man in jail, couple man still on the run, too,” he sang. Elsewhere in his catalog, however, Burna Boy plays a different character, a swaggering badmon with Hennessy to drink and haters to contend with.

The 25-year-old, born Damini Ebunoluwa Ogalu in Port Harcourt, Nigeria, has been making music since he was 10 — so he’s had plenty of time to try on different sounds and identities. After a classmate at his Montessori school gave him a copy of the production software FruityLoops, he’d spend time holed up in a cupboard with an old computer, teaching himself how to turn ideas into beats. But it wasn’t until he moved to London for university — and then, after two aimless years, dropped out and returned to Nigeria — that Burna Boy decided to double down on music. “I knew I didn’t want to be in school, but I didn’t know what I did want,” he said. “I just knew everything I didn’t want is what I had,” he said.

"The only thing you really see about Africa is ‘Help a child’ or some shit like that. I just wanted to listen to DMX."

In 2010, when he was 19 and in need of studio time, he drove

three hours to Nigeria’s oil-rich southern coast, where a friend of a

friend had a recording space. The studio, it turned out, sat high in the

trees, above a maze of petrol pipelines. It belonged to LeriQ, a

little-known producer who became Burna Boy’s first collaborator when he

crafted the clattering beat for “Like to Party,” the 2012 song that started Burna’s local buzz.

Around that time, having newly returned to Nigeria, Burna Boy began to take an interest in his culture, which he’d once written off in favor of glossy American cultural exports. “When you’re young, it’s not something that you’re proud of,” he said. “We watch TV and the only thing you really see about Africa is ‘Help a child’ or some shit like that. I just wanted to listen to DMX. I didn’t really appreciate Africanisms like that.” But as an adult, he reconnected with his roots. “I started knowing more about who I was, where I come from, and where my father’s father comes from. When people are singing my lyrics, you can see the emotion because they can relate to what I’m saying — ‘no money, no life, no water.’” It was that same openness to self-discovery that spawned the mishmash of genres in his music today, itself a rediscovery of the soundtracks of his upbringing: the hip-hop and R&B he heard everywhere, the reggae and dancehall records his dad would play, and the political afrobeat favored by his grandfather, who was Fela Kuti’s first manager.

To make it in Nigeria’s blossoming afropop industry, Burna Boy developed a brash persona that he described as being healthily skeptical of industry politics but that press and fans have interpreted as dickishness. He also came up with a unique strategy: taking note of its potential market size of over a billion people, he’d decided to concentrate his efforts on Africa. He toured the continent, collaborated with hip-hop artists from South Africa, and refused to follow the common practice of paying American or British artists above market rate for a verse or a hook. “At the end of the day, if you’re not selling yourself short as an African, everything you thought you needed to pay for will come to you,” he said, exasperated by what he thought was an obvious point. “You have the wave. You are you.” He was right — and now that he’s cultivated a fanbase impressed with his idiosyncratic take on Nigerian music, Burna Boy is ready to aim beyond Africa. “I’m an international rock star,” he said. “Now the music will travel without passports.”

Around that time, having newly returned to Nigeria, Burna Boy began to take an interest in his culture, which he’d once written off in favor of glossy American cultural exports. “When you’re young, it’s not something that you’re proud of,” he said. “We watch TV and the only thing you really see about Africa is ‘Help a child’ or some shit like that. I just wanted to listen to DMX. I didn’t really appreciate Africanisms like that.” But as an adult, he reconnected with his roots. “I started knowing more about who I was, where I come from, and where my father’s father comes from. When people are singing my lyrics, you can see the emotion because they can relate to what I’m saying — ‘no money, no life, no water.’” It was that same openness to self-discovery that spawned the mishmash of genres in his music today, itself a rediscovery of the soundtracks of his upbringing: the hip-hop and R&B he heard everywhere, the reggae and dancehall records his dad would play, and the political afrobeat favored by his grandfather, who was Fela Kuti’s first manager.

To make it in Nigeria’s blossoming afropop industry, Burna Boy developed a brash persona that he described as being healthily skeptical of industry politics but that press and fans have interpreted as dickishness. He also came up with a unique strategy: taking note of its potential market size of over a billion people, he’d decided to concentrate his efforts on Africa. He toured the continent, collaborated with hip-hop artists from South Africa, and refused to follow the common practice of paying American or British artists above market rate for a verse or a hook. “At the end of the day, if you’re not selling yourself short as an African, everything you thought you needed to pay for will come to you,” he said, exasperated by what he thought was an obvious point. “You have the wave. You are you.” He was right — and now that he’s cultivated a fanbase impressed with his idiosyncratic take on Nigerian music, Burna Boy is ready to aim beyond Africa. “I’m an international rock star,” he said. “Now the music will travel without passports.”